WhatsApp is a secure and popular messaging app with over 2 billion users worldwide. On average, users spend 19.4 hours monthly, sending more than 100 billion messages daily—a 54% rise since 2018.

As system designers, we must think about how fast users are growing.

WhatsApp is a good example to study.

Some key questions are:

- How is WhatsApp designed?

- How does it actually work?

- What components make up the system?

- How can it support billions of users at the same time?

- How does it keep user data safe and secure?

Functional Requirements

Conversations:

- Support one-to-one chats.

- Support group chats.

Acknowledgment:

- Show message status: sent, delivered, and read.

Sharing:

- Allow sharing of images, videos, and audio files.

Chat Storage:

- Store chat messages even if the user is offline.

- Deliver messages once the user comes online.

Push Notifications:

- Notify users about new messages when they are offline.

- Deliver notifications as soon as they are online.

Non Functional Requirement

Low Latency

- Messages should be delivered quickly with minimal delay.

Consistency

- Messages must appear in the same order they were sent.

- Chat history should stay the same across all devices.

Availability

- The system should always be accessible.

- In some cases, availability may be sacrificed to maintain consistency.

Security

- All messages must use end-to-end encryption.

- Only the sender and receiver can read the content, not even WhatsApp.

Scalability

- The system must handle a growing number of users.

- It should support billions of messages per day.

Resource estimation

WhatsApp is the world’s most widely used messaging app.

It has over 2 billion users globally.

Users exchange more than 100 billion messages per day.

Storage estimation

- 100 billion message, lets consider 90 billion text, 5 billion image, 5 billion video shared every day

- Let say average message size is 50 char which is 50*2 = 100 Bytes

- 100 bytes * 100 billion = 10 TB (remember 1 billion * 1 KB = 1 TB)

- Image average size is 2 Mb: 2 Mb * 5 Billion = 10 PB ( 1 MB * 1 Billion = 1 PB)

- Image average size 100 Mb: 100 MB * 5 Billion = 500 PB ( 1 MB * 1 Billion = 1 PB)

- Total Storage ~ 511 PB

Bandwidth Estimation

- 100 billion message, let say shared to 2 people minimum

- 200 billion query / day

- 200 Billion / 86400 = 2300K QFPS (1 Billion req /day = 11.5K QPS)

- Standard Server capacity is 64 K QFPS typically 32-core CPU, 128 GB RAM, NVMe SSDs, 10 Gbps network, plus caching and load balancing.

- No of Server = 2300 / 64 = 35 Server

API Design

sendMessage(message_ID, sender_ID, receiver_ID, type, text=none, media_object=none, document=none)

getMessage(user_Id)

uploadFile(file_type, file)

downloadFile(user_id, file_id)

High-level Design

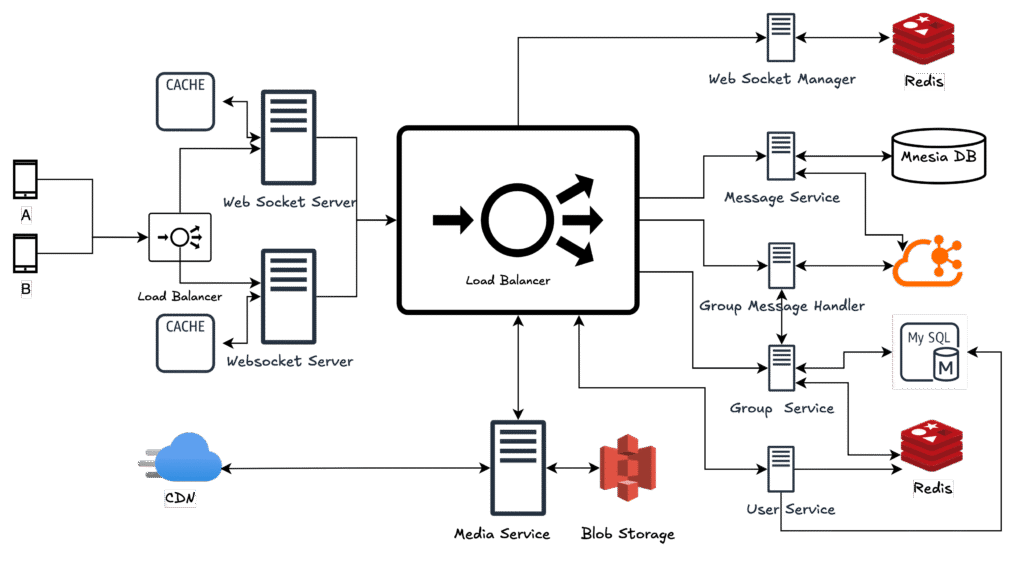

Detailed Design

What’s missing from the high-level design?

- How do clients and servers create a communication channel?

- How can the design scale to billions of users?

- Where and how is user data stored?

- How do we identify the correct receiver for a message?

Let’s dive into the high-level design and examine each component in detail.

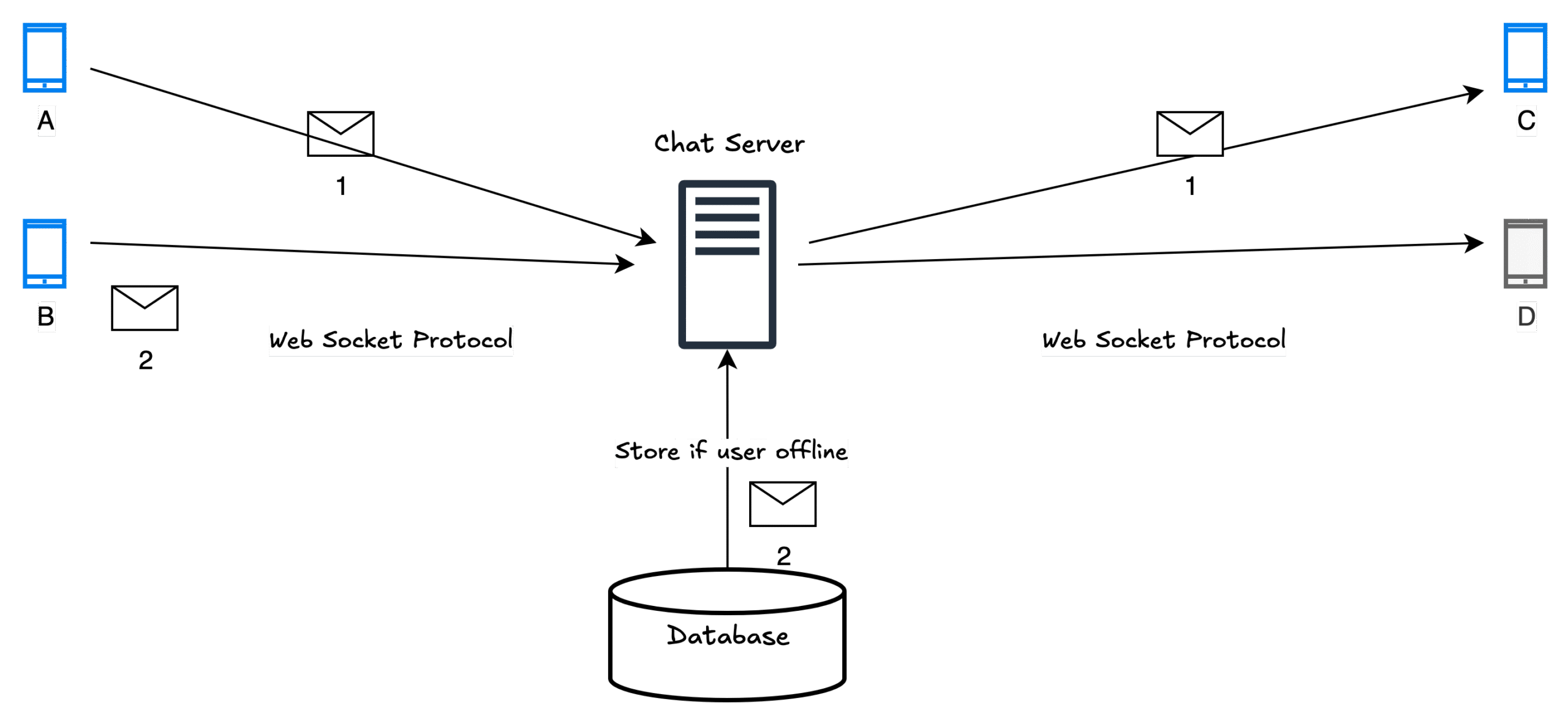

When you open WhatsApp on your phone, something interesting happens behind the scenes. Your device doesn’t just send messages blindly—it first establishes a persistent connection with a WebSocket server using the WebSocket protocol. Unlike traditional HTTP, this connection stays open, allowing instant, two-way communication.

But here’s the catch: one server cannot handle billions of people chatting at the same time. That’s why WhatsApp has many WebSocket servers, each responsible for keeping connections alive. Every online user gets a port, and the information about which user is connected to which server and port is carefully maintained in a central place called the WebSocket Manager, which sits on top of a Redis cluster. Think of Redis as a super-fast phone directory that helps find where each user is currently connected.

Sending and Receiving Messages

Now, imagine User A wants to send a message to User B. Here’s how the story unfolds:

- User A sends the message to their WebSocket server.

- That server checks with the WebSocket Manager to find where User B is connected.

- If User B is online, the manager immediately points to their server.

- If User B is offline, the message takes a different route.

- At the same time, the message is also stored in the Message Service, which sits on top of a special distributed database called Mnesia.

- Mnesia is designed for fast lookups, high fault tolerance, and quick deletion of old messages.

- Messages are stored temporarily (FIFO order) and deleted once delivered—or after 30 days if undelivered.

- If B is online, their WebSocket server picks up the message and delivers it instantly. If B is offline, they’ll receive it when they come back online, often via a push notification.

To make this smoother, each WebSocket server keeps a small cache of recent connections so it doesn’t always need to ask the WebSocket Manager. For example, if A and B are chatting continuously, the servers already know each other’s location.

Sharing Media Files

Text is light, but media—like photos, videos, and documents—are heavy. To handle this, WhatsApp uses a dedicated Asset Service. Here’s the process:

- The media file is compressed and encrypted on the sender’s phone.

- It is uploaded to blob storage via the Asset Service.

- To avoid duplication, a hash is generated. If the file already exists, WhatsApp just reuses the existing copy.

- The Asset Service generates a unique file ID and passes this ID to the receiver via the Message Service.

- The receiver then downloads the media directly from storage using the ID.

- If a particular file is requested too often, the Asset Service caches it in a CDN for faster delivery.

Group Messages

Groups are trickier. Not everyone in a group is online at the same time. Here’s how WhatsApp handles it:

The Group Message Handler queries the Group Service, gets the list of members, and then delivers the message to each user, just like a WebSocket server would.

When User A sends a group message, it goes first to the Message Service.

The message is then pushed into Kafka, which acts like a message bus. In Kafka terms:

The group = a topic.

Senders = producers.

Group members = consumers.

The Group Service (on top of a MySQL cluster with Redis caching) maintains full group details: IDs, members, icons, status, etc.

Validate Non Functional Requirement

The system is designed to meet key non-functional requirements: low latency, consistency, availability, security, and scalability.

- Low Latency

- Use geographically distributed WebSocket servers with caching.

- Add Redis cache clusters on top of MySQL clusters.

- Use CDNs for fast delivery of media and documents.

- Consistency

- Ensure message order with a FIFO messaging queue.

- Use a Sequencer to assign IDs and maintain causality.

- Store offline messages in the Mnesia database queue and deliver in order when users reconnect.

- Availability

- Deploy enough WebSocket servers with data replication.

- Re-create sessions via load balancer if a WebSocket server fails.

- Use Mnesia cluster with primary-secondary replication for durability and availability.

- Security

- Apply end-to-end encryption so only sender and receiver can read messages.

- Scalability

- One server can handle ~10 million connections.

- Add or remove servers dynamically as load changes.

Trade-offs in WhatsApp’s Design

Even though the system meets functional and non-functional requirements, there are two key trade-offs:

- Consistency vs. Availability

- CAP Theorem: During network failures, a system can guarantee either consistency or availability, but not both.

- WhatsApp’s Choice:

- Message order is very important.

- Prioritize consistency (messages must stay in order).

- Accept reduced availability in rare failure cases.

- Latency vs. Security

- Low Latency: Users expect real-time message delivery.

- Security Requirement: End-to-end encryption ensures messages are private.

- Trade-off:

- Encryption/decryption of text, images, videos, and audio adds processing time.

- This may increase latency, especially for large multimedia files.

- WhatsApp’s Choice:

- Prioritize security over ultra-low latency.

- Accept slight delays for safe message transmission.

Summary

- We designed a WhatsApp messenger system.

- Steps we covered:

- Identified functional and non-functional requirements.

- Estimated key resources (storage, bandwidth, servers).

- Designed both high-level and detailed architecture.

- Explained components and their roles in the system.

- Evaluated how the system meets non-functional requirements.

- Discussed important trade-offs (consistency vs. availability, latency vs. security).

- Key takeaway:

- General-purpose servers can be optimized for large-scale systems.