Two students try to collaborate on a report by sending drafts back and forth, but they quickly realize this approach is disorganized and inefficient.

Online collaborative document editing services like Google Docs solve the inefficiency of back-and-forth sharing by enabling real-time editing, reviewing, and commenting. They require no special hardware, allow access from anywhere, provide version history, and are often free. Alternatives include Etherpad, Office 365, and Slite.

- A collaborative editor can be built two ways:

- Centralized (client–server): a server hosts documents and clients connect to it.

- Peer-to-peer: users sync edits directly with each other.

- Most commercial systems choose client–server for better control and reliability — so this chapter focuses on that design.

- Quick fact: 64% of people use Google Docs at least once a week (survey).

Functional requirements

- Collaboration : Multi user should be able to collaborate together editing same document.

- Conflict Resolution : System should push all the changes to all editing users and resolve conflict if the edit on same segment of document.

- Suggestion: System should suggest completion word , spelling mistake correction, and gramatical errors.

- View Count : System should record vew count to be seen by admin

- History: Also the document history should be recorded to undo or revert to version.

A real-world document editor also has to have functions like document creation, deletion, and managing user access. We focus on the core functionalities listed above, but we also discuss the possibility of other functionalities in the lessons ahead.

Non-functional Requirements

- Latency: Keep response times low, even when users connect from different regions.

- Consistency: Ensure conflict resolution so all users see a synchronized and correct document state.

- Availability: Service must remain robust and accessible at all times.

- Scalability: Support large numbers of concurrent users creating or editing documents simultaneously.

Resource estimation

- We assume that there are 80 million daily active users (DAU).

- The maximum number of users able to edit a document concurrently is 20.

- The size of a textual document is 100 KB.

- 30% of all the documents contain images, whereas only 2% of documents contain videos.

- The collective storage required by images in a document is 1 MB, whereas each video is 3 MB.

- A user creates 1 document in one day.

Storage estimation

- Total number of documents in a day: 80M × 1 document in a day

- Storage for each textual document: 80M×100KBs = 8TBs

- Storage required for images for one day: 80M × 30/100 × 1 Mb = 24TBs (Thirty percent of documents contain images.)

- Storage required for video content for one day: 80M × 2/100 × 3 Mb = 4.8TBs (Two percent of documents contain videos.)

- Total = 8 + 24 + 4.8 = 36.8 TB /Day

Bandwidth estimation

- 36 TB / 86400 ~ 4 Gbps

Number of servers estimation

- Servers needed at peak load=80 million /64,000 = 1250 ≈ 1.3 K servers

High Level Design

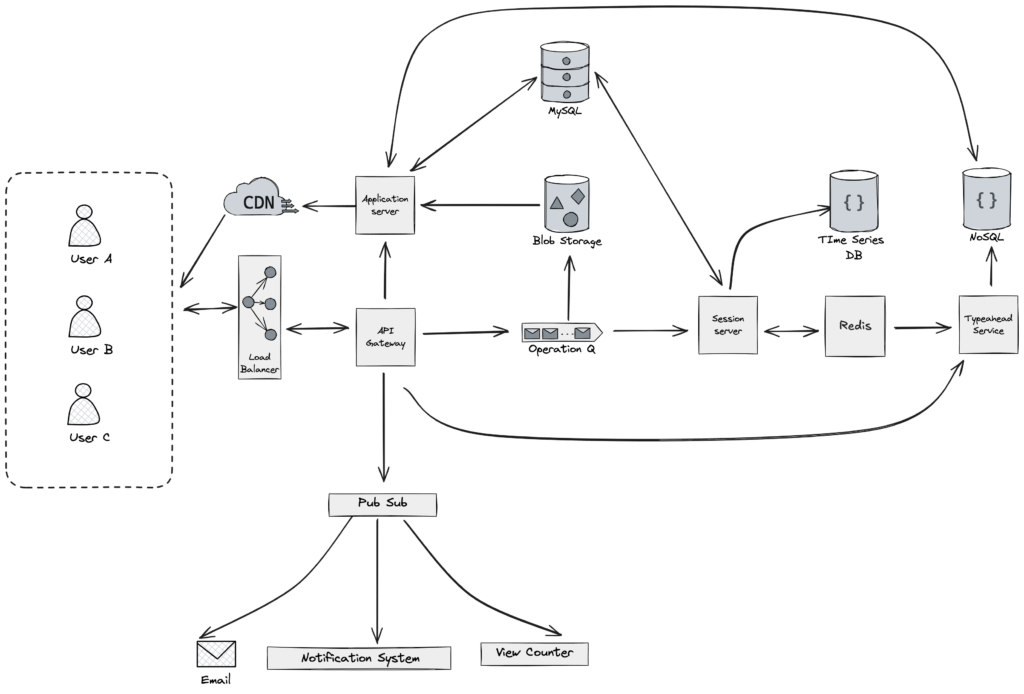

Components

API Gateway

- Usage: Routes edit requests (text, images, videos) into the system.

- Challenge: Needs to handle high-frequency small edits efficiently.

- Mitigation: Use WebSockets for live updates, batch requests before passing downstream.

Processing Queue

- Usage: Buffers edits (characters, media, comments) before processing.

- Challenge: If history is indefinite, the queue may grow large.

- Mitigation: Use batch processing + diff storage to reduce load.

Application Servers

- Usage: Convert documents (e.g., .doc ↔ .pdf), handle version comparisons, and extract features for recommendations.

- Challenge: More computation needed as history grows (e.g., comparing large diffs).

- Mitigation: Offload old history processing to background jobs; cache frequent diffs in Redis.

Data Stores

- Relational DB: Stores user info, document metadata, and access control.

- Time-Series DB: Stores fine-grained edit history (characters, timestamps).

- NoSQL DB: Stores comments for quick access.

- Blob Storage: Stores videos, images, large media versions.

- Distributed Cache (Redis): Stores frequently accessed document versions and session info.

- CDN: Delivers heavy objects (images, videos) quickly to users.

- Challenges:

- Time-series DB grows endlessly → higher storage costs.

- Blob storage bloats with media history.

- Querying large histories slows performance.

- Mitigations:

- Tiered storage → recent history in DB, older history archived to cheaper storage.

- Compression/deduplication → store only diffs between versions.

- Retention policies → allow admins/users to prune history.

Session Servers

- Usage: Maintain user sessions, access privileges, and editing rights.

- Challenge: If indefinite history is tied to permissions, complexity increases.

- Mitigation: Store metadata only in sessions, link to history in time-series DB.

Pub-Sub (Kafka, etc.)

- Usage: Handles notifications (e.g., “user X edited this document”).

- Challenge: Large edit history generates lots of events.

- Mitigation: Use filtering & batching so not every micro-edit triggers a full event.

Monitoring & Logging Services

- Usage: Track system health and debugging.

- Challenge: Logging every single edit forever = huge log data.

- Mitigation: Rotate logs, keep summaries/aggregates instead of raw data forever.

Workflow

Requests arrive at the API gateway → Think of this as the main door where all document editing requests first knock.

Collaborative editing & conflict resolution

- Requests go into a queue.

- If two people edit the same thing, conflicts are solved here.

- Once clean, the edits are stored in a time-series database.

- Images/videos get compressed; text gets stored right away.

History & recovery

- Every change is saved as a version.

- You can roll back to older versions or compare changes using “diffs.”

Asynchronous stuff (background tasks)

- Things like notifications, emails, comments, or view counts don’t block editing.

- These are sent to a pub-sub system (like Kafka) to be handled later.

Smart suggestions

- A typeahead service gives autocomplete for words/phrases.

- It uses a NoSQL database for storing big word lists.

- Commonly used words/phrases are kept in Redis for fast suggestions.

Import & export documents

- Application servers handle file conversions (e.g., .doc → .pdf).

- They also help extract keywords for the typeahead system.

Concurrency in Collaborative Editing

When multiple users edit the same part of a document, conflicts occur—like overlapping inserts or duplicate deletes. To solve this, conflict resolution must ensure commutativity (order doesn’t matter) and idempotency (same operation applied once).

Techniques for conflict resolution

Two main techniques are used: Operational Transformation (OT) and CRDTs.

Operational Transformation (OT)

Operational Transformation is a technique used in collaborative editing systems (like Google Docs) to handle concurrent edits.

It works by transforming the position or intent of operations (insert, delete, update) when they conflict, so that all users end up with the same final document in spite of edits happening at the same time.

- Example: If two users insert text at the same place, OT shifts one operation’s position so both changes appear consistently.

Let’s learn through example with Operational Transformation (OT):

Initial text: “My name is “

Case :

- User A wants to write

"Ram" - User B wants to write

"Shyam"

Both type at the same cursor position (end of sentence), at the same time.

Step 1: Record operations

- A’s operation = Insert(“Ram”, pos=11)

- B’s operation = Insert(“Shyam”, pos=11)

Step 2: Conflict (both insert at pos=11)

OT now applies transformation functions so the operations can co-exist.

Rule: If two inserts happen at the same place, system orders them deterministically (e.g., by timestamp or user ID).

Step 3: Transform operations

- If A’s operation is applied first:

- Text becomes

"My name is Ram" - Now B’s operation (Insert(“Shyam”, pos=11)) must be transformed → since

"Ram"is already inserted, B’s insert shifts to pos=14. - Final text:

"My name is RamShyam"

- Text becomes

- If B’s operation is applied first:

- Text becomes

"My name is Shyam" - A’s operation shifts to pos=16 (after

"Shyam") - Final text:

"My name is ShyamRam"

- Text becomes

Step 4: Convergence

No matter the order, both users end up with the same consistent final document, just differing in the order of words (based on the transformation rule).

Final Possible Outputs:

"My name is RamShyam""My name is ShyamRam"

(depending on system’s deterministic tie-break rule).

Conflict-free Replicated Data Type (CRDT)

Conflict-free Replicated Data Type is a special kind of data structure designed for distributed systems where multiple users can update data at the same time.

CRDTs automatically resolve conflicts using mathematical rules and unique identifiers for every operation, so that no matter the order of operations, all replicas converge to the same final state without needing a central server.

- Example: Each character in a text editor can be given a unique ID, and merges are done based on those IDs instead of shifting positions.

Initial text: “My name is “

Case Setup

- User A inserts

"Ram"at the end. - User B inserts

"Shyam"at the same position (end).

Both edits happen concurrently.

How OT Handles It

- User A: Insert(“Ram”, pos=11)

- User B: Insert(“Shyam”, pos=11)

Conflict → Both insert at pos=11.

OT resolves by transforming one operation’s position based on the other.

- If A wins first →

"My name is RamShyam" - If B wins first →

"My name is ShyamRam"

Final result: One of the two orders, chosen deterministically.

How CRDT Handles It

CRDT works differently. Each inserted character gets a unique identifier (ID) (based on user + timestamp/logical clock).

Example:

"R"might get ID<A,1>,"a"=<A,2>,"m"=<A,3>"S"=<B,1>,"h"=<B,2>,"y"=<B,3>…

Now, when merging:

- CRDT doesn’t “shift positions.”

- Instead, it merges characters based on their IDs and ordering rules (e.g., user priority or timestamp ordering).

So final text might be:

"My name is RamShyam"(if A’s IDs sort before B’s IDs)"My name is ShyamRam"(if B’s IDs sort before A’s IDs)

Key Difference

- OT = adjusts positions dynamically using transformation functions (shifts operations).

- CRDT = assigns each piece of content a unique ID, then merges based on deterministic ordering — no shifting needed.

Both guarantee convergence → everyone sees the same final document.

But:

- OT = needs a central server (or coordination) to transform.

- CRDT = works peer-to-peer too, no central coordination.

Although well-known online editing platforms like Google Docs, Etherpad, and Firepad use OT, CRDTs have made concurrency and consistency in collaborative document editing easy. In fact, with CRDTs, it’s possible to implement a serverless peer-to-peer collaborative document editing service.

Note: OT and CRDTs are good solutions for conflict resolution in collaborative editing, but our use of WebSockets makes it possible to highlight a collaborator’s cursor. Other users will anticipate the position of a collaborator’s next operation and naturally avoid conflict.